“There’s an app for that” was a popular phrase thrown around a few years ago. The phrase optimistically noted that in this technological era, whatever task was at hand, you could probably find an app on your pocket-carried supercomputer that would help you right out.

What the phrase did not include was the notion that in order to get said app, you had to open the app store, search, pick the right one, possibly pay 99¢, type in your app store password, wait for it to download, open the app, grant permissions to contacts, location or whatever else the app might want until finally you could use the app. Unless you had to register and/or sign in to use it, possibly add a credit card.

Apps were revolutionary for their time, no doubt. But in a world where cars drive themselves and pizzas are best ordered from your watch, some of the qualities of apps as we know them are starting to seem a bit menial. The numbers seem to suggest this as well, as apparently half of U.S. smartphone users download zero apps per month.

At its most atomic scale, an “app” is a little window on your phone that does things your operating system might not do on its own. When the iPhone was first introduced, the phone dialer was presented as “just another app”. It was no different, it was suggested, than any other apps you’d install, and every app added new features to your phone.

But what about replacing features? What about augmenting features? Sure, WhatsApp can create a dialer app that lets you call using their service instead of the cell network. But they’ll lose out on all kinds of systems integration into the OS: what if someone calls you, can you answer with WhatsApp?

It varies from platform to platform the amount of integration apps are allowed to do. While iOS is mostly closed down, you can still replace the keyboard. Android allows you to replace many aspects such as the browser, and yes, the dialer as well. But even then Android is still very much Google’s platform, and there are key aspects of the operating system that are still off-limits.

Apps of today are also very much hardware specific. Android apps look and behave a specific way and iOS apps look and behave a specific way. Some apps are cross-platform, available on both. This has worked fine for a world where people carry a smartphone in their pockets, but what happens when we stop doing that?

In order to speculate what the app of the future might look like, let’s summarize some of the challenges posed by the current interface:

- Finding and installing apps is cumbersome

- Having to manage your identity and sign into every app is a pain

- Having to remember or save passwords for every service is dangerous

- Trusting an app with your credit card information is both cumbersome and risky

- Generally, closed platforms are advantageous mostly for the platform vendors

- Future hardware categories are likely to demand drastically different or adaptive apps

If you’re Apple or Google, it might sounds like #5 — being the platform vendor — is a good place to be, and so it might dampen any initiatives to make new touch points that’ll fully open the home turf to competing apps. But there’s an argument to be made that they will have to, or be left behind.

Metaplatform

Enter Facebook. Most of the world is on it. They have your name, address, credit card, contacts, and probably photos. Facebook is you; it’s your identity, and you can use it to sign in, pay and communicate. Facebook is a metaplatform. So is Amazon, and so is Microsoft. Neither of these three have a mobile hardware play to speak of, but they have services and ecosystems you wouldn’t want to be without. To a certain extent, so do Google and Apple, but it’s a competitive space and Facebook arguably has the upper hand on the identity aspect, while Amazon has for the payment aspect. And so in five years maybe it doesn’t matter how good Apple Pay is if you can’t get your “Prime discount” when using it, and it doesn’t matter how good Google Duo is if none of your friends are using it.

People use Facebook. People use Amazon. People use them even if they have to use a browser to do so, and their webpages run well. More so, the secret sauce that makes them run well — React, AWS etc. — is available to anyone. To an extent it doesn’t matter which platform these run on — all they need is a browser. In five years time, will you care whether that browser runs on Android or iOS?

Apple and Google obviously care, and the thing they need to do in order for their platforms to be relevant in the metaplatform future, is open up. The platform that opens up the most integration touch points in their operating system will be able to provide the better user experience for your metaplatform of choice. People might choose Android simply because Facebook runs better on it.

In a future where apps run anywhere, the underlying platform becomes a checkbox. We’re already seeing the baby steps towards this with React Native, and progressive web apps.

Future Apps

So what might the app of the future look like? Perhaps a better question to ask is: how would the app of the future work?

A few problems need to be solved. Instead of installing a separate app for every airline you fly with, and only when you fly, then perhaps the website should be allowed to perform as well as were it actually native. If you fly that airline a lot — pin it — it’s now “installed”. Unpinning it uninstalls it. Identity wise, you are signed into your operating system with whatever cloud account you prefer. This cloud maintains your passwords and your credit cards. Through biometric authentication, apps can tap into this information when you allow it. No signups, no cumbersome passwords to remember.

Increasingly, apps won’t install themselves as icons in a grid, but instead hook into touch points in the operating system and become actions for intents provided. It’s long been the case that the best apps are the ones that focus exclusively on solving very specific problems and tackling specific use cases. The ultimate refinement of this is the complete reduction into taking action based on a user intent.

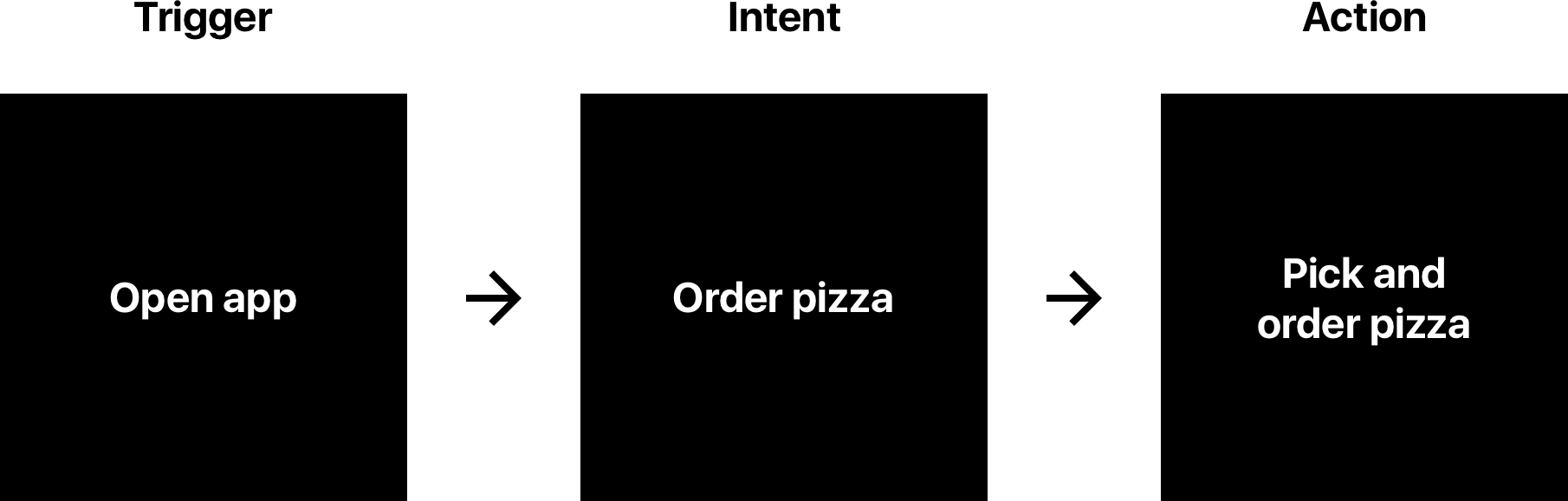

In comparison, the apps of today are very linear in their flow. You pick an app, pick an intent, complete your task:

When the intent of an app becomes available before the app itself is even launched, suddenly the flow to completing tasks can be highly streamlined:

Instead of hunting for icons, perhaps your homescreen will simply list intents contextual to location, time of day, and habits.

Intents also enable interoperability between apps. Some intents are present already today — on Android, the “share” intent lets you transport content from one place to another. Imagine every app as an intent-based action — the plug-in platform, where apps add, replace or augment any intent you might have. Call someone, text someone, take a note are all existing intents that apps can handle the actions for on Android. But who’s your digital assistant, and can it place a WhatsApp call when you ask it to?

The process will be gradual, but it’s likely to kill off most apps that aren’t able to transition to being simply actions. There’s going to be room for the occasional “pinned app” for use cases to which there aren’t universal handlers, or for apps that create new intents (“I want to tweet”), but those are likely to be exceptions.

When metaplatforms provide all the infrastructure and apps merely tap into them, will this make for a more closed web? That remains to be seen — could be that it becomes more open, as web-apps increase in what they can do and where they run. But one thing’s for sure — you’ll spend spend less time hunting and pecking between icons in a grid, as menial tasks are being handled by intents and actions. In fact we might finally be able to go to a dinner with friends without everyone putting their smartphones next to their plates. In this golden future, maybe that Swarm check-in is handled by your digital assistant.

The best user interface is invisible, and in the plug-in future there might not be a lot to look at. Apps are dead. Soon enough, there will be an action for that.

One response to “Apps Are Dead”

Very interesting approach, thanks for sharing your thoughts how apps can evolve in the near future 🙂